On The Prowl

These are a few of my favorite tropes: Hurt-comfort and “On the Prowl”

One of things I love most about media fandom is how it brings to the foreground the collaboration of not only different creators but also the impact of the audiences. After all, before we create fannish material, we consume the media texts—in turn loving and hating them, enjoying and dismissing them, interpreting and analyzing them. Any fan writer is first a reader/viewer, of the source texts but also, often, of other fan works. And any interpretation is, of course, first of all deeply personal, but part of being fannish often means that we share our feelings, and thus responses move from individual to collective reactions. Fandom can be an echo chamber of sorts—the highs are higher and the lows are lower. It also is a community where our emotional responses are shared and valued, where we don’t have to apologize for our kinks and squicks: our voyeuristic desires and narcissistic identifications are welcomed and often shared by other fans.

Often when outsiders first discover fandom they are stunned by certain genres and tropes. Male pregnancies, gender swaps, and mind bonds may occur in non-fannish art, but the popularity of these tropes is noteworthy. Even more so is the preponderance of what we call hurt-comfort, the inflicting of emotional or physical hurt on one or all of the protagonists to create an environment where that pain can be remedied via comfort. It’s one of my personal favorites, but looking at archives, it seems widely popular: on the Archive of Our Own, a good 8% of works are tagged by their authors as hurt-comfort and the tag has over 3 million bookmarks. It’s noteworthy enough that the first academic essay on fan fiction, Joanna Russ’s “Pornography By Women For Women, With Love!” (1985) describes it in detail. In her 1992 book-length anthropological study, Enterprising Women, Camille Bacon-Smith dedicates her final chapter to the genre, suggesting that it is the most intimate secret of media fandom; she announces that “at the heart of the [media fan] community something both more meaningful and more dangerous lay hidden” (269)—and she discovers it to be hurt-comfort.

Watching Sisabet and Sweetestdrain’s multivid “On the Prowl” suggests Bacon-Smith might have a point—at least as far as the vidders and many viewers (including myself) are concerned. Created for the “Self Portrait” Challenge for the 2010 VividCon, the vid is an illustration and analysis of certain parts of media fan culture as well as a challenge to all of its fannish viewer. The vid’s tag line in the program and when shared online is the provocative question “Where is our line?” Before we even begin watching, the summary challenges us viewers to consider our own viewing position. Even after watching the vid (once, twice, a dozen times…), the questions may remain unanswered. Did we turn away at the burnt corpse? Did we close our eyes when the fingernail gets pulled? But, most importantly, at what point does pleasure turn to shock turn to embarrassment?

The vid opens on its title card “On the Prowl” over the spoken words “I was thinking about picking up some…” The breathy pause on black is resolved by the words “young boys” with a first image of Taylor Lautner as sexy Twilight werewolf Jacob Black taking off his shirt. This sets up the entire video as an aggressive exploration of female sexuality and the female gaze. Lydia Lunch, the raspy female voice, is an artist who has been a radical voice the alternative scene for decades, doubling down on the predatory age difference implied in the words.

Given the popularity of hurt-comfort in slash fandom (quite often using the characters the vidders depict as suffering in “On the Prowl”) and the fact that the vid is framed as a “Self Portrait,” the vid is clearly by and for hurt-comfort fans. We can read On the Prowl as an investigation, an inquiry into the way many hurt-comfort fans (including clearly the vidder and including me) feel about the suffering they like their beloved protagonists to endure. From the predatory opening to the breathlessly hungry and ultimately horrifying repeated lyric “And then I wanted more,” the fanvid pushes us to (find) our limits. It may begin with bare skin, moving on to bruises without blood, but then it goes further and further and further. The clear progression, the repetition of similar types of abuse and torture, is a portrait of a community that is egging itself on; daring itself and each other to go bigger, to dare more. The video asks each of its viewers where their own lines are and how much hurt they enjoy in their hurt-comfort. Of course there are fans to whom this type of story does not appeal at all. And yet, the thin lines between hurt and sexuality, the doubling of images of severe pain to mimic images of sexual ecstasy can be found in fannish works even outside of hurt-comfort—though they are clearly much more prevalent in that genre.

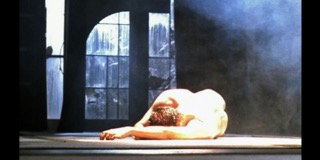

As the fast, aggressive electronic music start up, we are presented with an array of images of naked men from a variety of sources. Everything in this video is collaborative and transformative: the music is an original by Blow-Up, a DJ duo mostly known for their remixes, featuring the voice of Lydia Lunch. The vid uses clips from over 60 TV shows and films to draw our attention to the popular trope of heroic male suffering. As it stands and without any context, it could easily be misread as what fans often shorthand as “torture porn”—the voyeuristic enjoyment of fictional suffering. It singlemindedly progresses from buff naked men, to men fighting, to men getting bound and beaten and electrocuted and cut and burnt and tortured. For any casual viewer, it may be an indictment of media violence, but to a media fan it is so much more than that.

For one, we recognize many if not most of the guys and often the context of the clip: Angel coming back from hell in Buffy; Robert Downey Jr. in the boxing ring in Sherlock Holmes; David Tennant’s Doctor Who falling out of an airplane in order to fight the Master; James Bond getting tortured in Casino Royale; Torchwood’s Captain Jack getting cemented alive; Han Solo’s frozen face of agony; Hutch getting kidnapped and addicted to heroin; Captain Picard as the Borg; Sam’s fingernail getting pulled out on Supernatural; to name but a few that resonate with me personally. So the references are meaningful in and of themselves but also, of course, as they showcase a variety of media texts that love to beat up their heroes—and we love watching them get beat up.

The vid celebrates the way fan works often turn the gaze back at the men, thus objectifying them, reminiscent of other fanvids such as the Clucking Belles’ “A Fannish Taxonomy of Hotness (Hot Hot Hot!)” (2005). Both vids in fact use the same pattern of offering a series of shots where the heroes do the same thing or are in the same situation, reminding us of the tropes media uses and fans embrace. In “A Fannish Taxonomy of Hotness,” the tropes are varied, ranging from sword fighting and bare-knuckled fights to costume choices (black T-shirts, hats, dresses, straight jackets). But even though it features brief moments of fighting and suffering, the emphasis tends to be on the presentation of male bodies and the tropes that appealingly display them.

In contrast, “On the Prowl” zooms in on one narrow aspect of fannish desire—albeit an beloved and extremely personal one, the vidders suggest. “On the Prowl” focuses in only on the hurt, the torture, the suffering and only that of the male protagonists. It is these exact canon scenes, of course, that hurt-comfort fans use to jump off into their fan stories. How often does a fist fight between Mulder and Krycek lead the two to discover their underlying feelings? How often does Q help James Bond recover from the PTSD of the sexual torture he endured? There exists an entire subgenre of Starsky&Hutch post-addiction stories, and Angel dealing with hell is not only at the center of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Season 3, but also of any Angel-pairing written at that time. If “A Fannish Taxonomy of Hotness” reminds us that tropes are common and popular and already present in the source texts, “On the Prowl” reminds us that the shows repeatedly ask us to emphasize with (if not enjoy) the visual suffering of the central characters. Watching the progression of suffering invokes for me not only the individual scenes but also the stories that fix them—as well as all the other stories that harm my BSOs even further.

And yet, as some critics have observed, the fannish response to “On the Prowl” is very different to a vid like “Women’s Work,” also co-edited by Sisabet. Why do fans read “Women’s Work” as a strong exploration of violence against women in the media whereas “On the Prowl” performs similar violence against men yet isn’t read within the fan community in the same way? Is violence against women deplorable yet violence against men acceptable? Are primarily female slash vid fans only offended when the bodies bloodied and cut open are women? I’d suggest there’s something else at play, namely the identity of the victims. For anyone not deeply familiar with the show, it is initially difficult to recognize “Women’s Work” as a Supernatural vid. Most of the images are of female victims, monsters, or both that appear only briefly on the show. In other words, these characters are defined almost exclusively by the images of violence showcased in “Women’s Work.” (Being defiled and killed is, as the title wryly suggests, their JOB.)

In contrast, even though “On the Prowl” draws from over 60 shows, most media fans will recognize a fair number of the characters if not the exact shots, because they tend to be the protagonists! Not only is their suffering often meaningful to the narrative and the character development, they also rarely are characterized only in terms of it. The scenes where our heroes are bound, beaten, and bloodied quite often lead to their rescue, recovery, and revenge. And even the self harm, the half dozen shots of guys trying to eat their guns, must be read in this context: after all, viewers only connect emotionally with a character trying to commit suicide if we care about their life and understand what would bring them to the edge. After all, the suffering men featured in “On the Prowl” are the heroes of their stories.

Beyond the gender difference, however, the narrative thrust of the two vids is quite different. “On the Prowl” has a clear direction, where the violence intensifies, the tension increases, resulting in a crescendo of sound, images, and our responses. “Women’s Work,” on the other hand, offers two equally limited and equally harmful aspects of the representation of women in Supernatural (and, by extension, arguably in much of the media we consume): suffering victim or suffering monster, but never suffering hero. The first half of “Women’s Work” collects scared and tortured women, some of whose violent deaths (like Sam’s girlfriend and Sam and Dean’s mother) are the driving impetus for much of the series. The second half focuses on equally undercharacterized women who represent the monsters and villains the brothers fight against, and who are set up to be deservedly attacked and murdered. Like the madonna/whore dichotomy of old, this vid reminds us that usually only a few very narrowly defined roles are available for women.

With its focus on male characters, “On the Prowl” flips this narrative on its head. Most of the showcased bloodied tortured heroes are at the center of their shows and films, their excerpted scenes but a tiny part of a complex plot line and portrayal. We care as much about these specific characters suffering as we do about what they endure. We clearly know they survive, because we watch their shows, but even if they ultimately die in canon, we know there will be thousands of stories to revive them. Just like each fanfic is more meaningful because it resonates with canon and all the other stories we have read, so canon itself gains potential through all the fan stories with their myriad endings and alternate worlds that fandom has created.