A History of Vidding

Vidding is communal poetry. It weaves together familiar images and beloved characters with music to create an intimate emotional journey. Fanvids bypass our higher cognitive functions and aim straight for our limbic center: where we laugh, where we sing and where we cry.

Fan Vidding… In the beginning…

Fan vidding draws some of its origins from folk music which itself utilizes pre-existing and well-loved stories and myths and resets them to music. Until the invention of the moving picture, these re-imaginings remained aural, not visual. What makes fan vidding unique is the 20th century technology. This allowed ordinary consumers access both to the visual media (TV and media) as well as the audio and the ability to edit and reshape those sources. The introduction of that new and more accessible technology inspired multiple communities across the world to interact with moving images and sound in their own way.

- Discover what the Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields” has to do with the birth of modern media vidding?

- Hear how one fan’s “dowry” consisted of three boxes of Star Trek film clips.

- What DO you do with a drunken Vulcan?

- Be amazed that a vidding fan in 1980 would have had to shell out (in today’s US dollars) nearly $6000 to simply begin.

- Shiver at the terribleness of 5th and 6th gen.

- Behold the power of the stopwatch.

- Enjoy the antics of two 1977 role-playing Betamax salesmen.

- Keep an eye on the challenges of rainbow noise, flying erase heads, jog shuttles, and dirty frames.

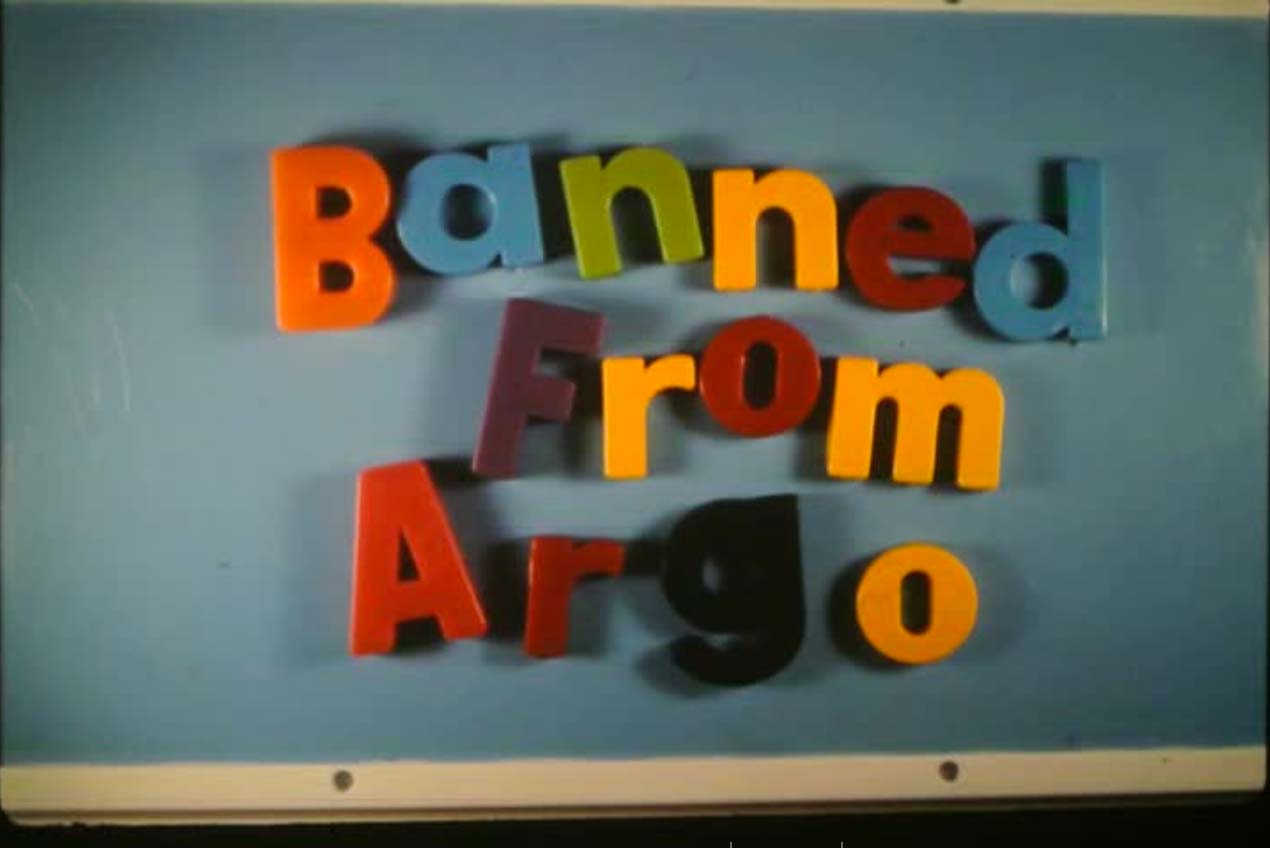

- Curse when a major vidding collective was driven even further underground by the actions of a well known professionally run convention.

- Boo and hiss at the word “Macrovision.”

- Also: the costs and challenges to early vidders, how technology shaped the storytelling, the power of feedback, language, and vocabulary, learning to structure a vidshow, thwarting the powers that be, and most importantly, the indispensability of mentors and community.

While there are robust vidding histories in anime and gaming fandoms, my “History of Vidding” focuses on a small slice of time and space: the community of women who were fans of TV and movies popular in the Western world and their contributions to vidding in the 1970s through the 1990s. As with most “history of” essays, it is prone to subjective memory, information available, and personal perspectives.

A long time ago, in a galaxy not that far away...

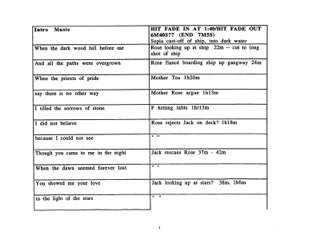

The creation of fanvids required two things: access to consumer-level audio-visual equipment and the average fan’s ability to obtain TV/movie video source. Commercial “music videos” or the “musical short” dates back to the 1920s, but popular musical artists began offering musical shorts in the late 1950s and early 1960s to help sell their music. It was the Beatles who, in 1967 took the concept of promotional videos to a new artistic height.

“The colour promotional clips for “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane”, made in early 1967 and directed by Peter Goldman, took the promotional film format to a new level. They used techniques borrowed from underground and avant garde film, including reversed film and slow motion, dramatic lighting, unusual camera angles and color filtering added in post-production.” Source: Wikipedia. See Strawberry Fields Forever on YouTube.

Kandy Fong, a Star Trek fan based in Phoenix, Arizona watched “Strawberry Fields Forever” and realized she could do something similar for her favorite TV show. Her soon-to-be husband had access to film clips from Star Trek TV episodes. These were actual clips of 35mm film that had been left on the Desilu Studios editing room floor during production of the series in the 1960s. These film clips were then mounted into slides and sold to collectors. In addition, Kandy had a slide projector carousel and a cassette tape player. She now had music, video, and source, the three main ingredients to making a fanvid.

During a 2012 interview with her long-time friend Marnie, Kandy explained:

Kandy Fong: The Beatles did a music video for “Strawberry Fields.” Where they were doing things like jumping out of trees, and then this long piano, that went up— the strings went up into the tree, and they were doing all sorts of things. They weren’t standing there and playing instruments, which was all the music videos you’d seen to date. And I thought, duh. This guy I’m dating has the cigar boxes full of little pieces of film from Star Trek. I’ll betcha I could put those together and tell a story.

Marnie: Off-cuts, yes.

KF: And, because the local Star Trek club in Phoenix, which is the longest-running fan club in the world, United Federation of Phoenix — thank you, I named it— (laughter) Umm— needed entertainment. I figured, well, let’s put together a little show. So I said, “Hey. Hey, best friend. Hey, hey, future husband— (laughter) —let’s get this idea, and put together a show.

MS: [He] had no idea what he was getting into.

KF: I know. That was his dowry. The three cigar boxes full (of Star Trek film clips).

Source: Media Fandom Oral History Project Interview with Kandy Fong and Marnie S (2012)

Listen to a five minute excerpt from Kandy Fong’s 2012 interview about the inspiration for the first fanvids and how Gene Roddenberry helped support them. The entire 90 minute interview is archived at the University of Iowa: Kandy Fong and Marnie oral history interview, Escapade convention, Ventura, California, February 24, 2012 [transcript ↓]

Transcript

KF: ….. music videos.

MS: Yes.

KF: ‘Cause I remember Mary Van Deusen—

MS: Yes—

KF: —brought a bunch of those.

MS: —Mary Van Deusen brought a bunch, and we began showing videos I think at the second IDICon.

KF: Was it the second one?

MS: Yeah. I think it started with the second, and those, when you look back now, of course, the technical quality is like totally, totally different. But, yes. They began. They were starting right then and there. Yeah. It was the second IDICon.

I: So, I’m curious, where, I mean, you did the slide shows that were the first thing that kind of led to the entire institution of vidding, really. Where did that come from? I know that other people, like obviously, did slide shows of other sorts, but not what you were doing.

KF: Okay. The Beatles did a music video for “Strawberry Fields.” Where they were doing things like jumping out of trees, and then this long piano, that went up— the strings went up into the tree, and they were doing all sorts of things. They weren’t standing there and playing instruments, which was all the music videos you’d seen to date. And I thought, duh. This guy I’m dating has the cigar boxes full of little pieces of film from Star Trek. I’ll betcha I could put those together and tell a story.

MS: Off-cuts, yes.

KF: And, because the local Star Trek club in Phoenix, which is the longest-running fan club in the world, United Federation of Phoenix — thank you, I named it—

(laughter)

KF: Umm— needed entertainment. I figured, well, let’s put together a little show. So I said, “Hey. Hey, best friend. Hey, hey, future husband—

(laughter)

KF: —let’s get this idea, and put together a show.

MS: John had no idea what he was getting into.

KF: I know. That was his dowry. The three cigar boxes full.

MS: (laughter)

KF: As well as the fact that he had all the episodes on three-quarter-inch tape. Professional one-inch tape. (unintelligible)

MS: One-inch tape. So you knew he was a keeper, then.

KF: Yeah. Definitely. So, I decided that let’s do a thing there, I did a funny little thing where, uh, “What Do You Do With a Drunken Vulcan,” I did a little thing of that.

MS: Yes, I remember that.

KF: Then I did a little story about Ensign Fong aboard the Enterpr—, a very Mary Sue story. Y’know, very little story, I just illustrated it. And as a club we were all gonna go over to the very last IDICon Film Con that Bjo Trimble was doing. And her husband was going to be coming to Phoenix for something with his job. And I wrote to her, and said, “Hey, I have this thing I’d love to show at your convention.” And she says, “Well, hey, I’m going to be coming in town with my husband, why don’t you show it to me?” So I did. She says, “Cool.” I ended up taking it to the convention and they put us in this little room at the bottom. And she says, “Oh, I’m sure this’ll be a couple of people will want to see it.” Well, it had only like thirty-five people I think that could fit into the room. So they ran it in a loop, for eight hours. People would see it, get out, go back in line again, and then stand in line for an hour and a half so they could see the seven-minute thing again. And so that’s— I knew there was a hunger for it. So, I had met Gene Roddenberry previously, ‘cause he was in Phoenix giving a speech and I was president of the Star Trek club, so I got to meet him. It’s complicated, I’ll tell the story another time. So, when he was there, I kinda say, “Hi! I’m glad to see you. By the way, would you sign my, y’know, my club badge, so I’m officially a fan of yours,” and he did. And he— and I says, “By the way, I have this idea of putting together a slide show.” He goes, “Oh, that’s a great idea. I’ve been trying to convince Paramount that there’s enough fan interest in a movie.” And I said, “Great.” So I’m writing to him eventually, and he ended up writing back to me, and oh, I have it in writing, that I can do these slide shows. And in fact, in the future years I ended up visiting a couple of times at Paramount. And he gave me actual slides that were publicity shots, et cetera, from the various sets, so that I could kind of expand my slide shows, and show more.

MS: I went with you.

KF: Exactly. You were there too.

MS: I went the first time.

KF: Yeah.

MS: That was before we moved out here.

KF: That’s true. But— So I really got a chance to get— People liked it……

What Do You Do With A Drunken Vulcan? An Early Media Fanvid:

One of the first live-action fanvids was a short comedy about the character of Mr. Spock set to a filk song “What Do You Do With a Drunken Vulcan?” It was shown in 1975 at a meeting of The United Federation of Phoenix, a Star Trek fan club. Kandy selected film clips that she felt advanced the story and arranged them in order in the slide carousel. She then manually started the cassette tape player and followed the lyrics along using a script or storyboard and “clicked” the projector to advance each slide. These early fanvids were very much like performance art, as they were done live, were not recorded, and the timing of the clicks had to match the lyrics.

In April 1976, Kandy took her “little illustrated stories” to Equicon, a Los Angeles based science fiction convention with a heavy Star Trek presence:

“As a club we were all gonna go over to the very last Equicon/Film Con that Bjo Trimble was doing… And I wrote to her, and said, “Hey, I have this thing I’d love to show at your convention.” And she says, “Well, hey, I’m going to be coming in town with my husband, why don’t you show it to me?” … I ended up taking it to the convention and they put us in this little room at the bottom. And she says, “Oh, I’m sure this’ll be a couple of people will want to see it.” Well, it had only like thirty-five people I think that could fit into the room. So they ran it in a loop, for eight hours. People would see it, get out, go back in line again, and then stand in line for an hour and a half so they could see the seven-minute thing again. And so that’s— I knew there was a hunger for it.”

Source: Media Fandom Oral History Project Interview with Kandy Fong and Marnie S (2012)

The slideshows were not only popular with fellow fans. Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, had been supportive of this sort of fan creativity and engagement for many years. He and his production office had received copies of the first Star Trek fanzine, Spockanalia, and he regularly attended fan conventions. So, when Kandy ran into Gene Roddenberry at Equicon in 1976, she mentioned her slideshows:

“So, when he was there, I kinda say, “Hi! I’m glad to see you. By the way, would you sign my, y’know, my club badge, so I’m officially a fan of yours,” and he did. And he— and I says, “By the way, I have this idea of putting together a slideshow.” He goes, “Oh, that’s a great idea. I’ve been trying to convince Paramount that there’s enough fan interest in a movie.” And I said, “Great.” So I’m writing to him eventually, and he ended up writing back to me, and oh, I have it in writing, that I can do these slideshows. And in fact, in the future years I ended up visiting a couple of times at Paramount. And he gave me actual slides that were publicity shots, et cetera, from the various sets, so that I could kind of expand my slide shows, and show more….”

Source: Media Fandom Oral History Project Interview with Kandy Fong and Marnie S (2012)

In later years, Kandy filmed some of her slideshows for Roddenberry.

To watch a fanvid is to have a simultaneous three-way conversation with your eyes, your ears and your brain. And it all takes place within a densely packed four minutes. It is like a haiku on fast forward.

At this point, without a means of recording the TV shows or movies and with no private sales of film to consumers, there was no way for fans to access the visual source. Even if fans could access the source, they lacked the ability to edit the source. Vidders were like painters trying to create without paint, brush or canvas. Or to paraphrase Mr. Spock: “They were living in an era of stone knives and bearskins.” This meant that for these first few years, fanvids were limited to slideshows and accompanying audio provided by cassette tape players. It would take the invention of the VCR and its eventual mass marketing to empower fan vidders to add moving images to their creations.

In September 1975, Betamax became the first videocassette recorder to enter the consumer market. Sony’s Betamax VCR recorder was combined with a 19-inch color TV and sold for $2,495, or around $11,000 in today’s dollars. There were, of course, additional expenses, such as blank cassette tapes: in 1977, the price of a single blank tape was $20 ($72 in today’s dollars).

By 1980, the VCR’s price had fallen to $1000, or $2800 in today’s dollars.

The cost of owning a VCR, however, was clearly out of reach for most fans, many of whose ages ranged between the teens to their 30s and were either just out of school or starting families.

Sony Promotional Video for the first consumer Betamax player sold in the US, the SL-6200 (1975), which was only available as single integrated unit with the Sony color TV console LV-1901. Star Trek makes a brief appearance at 03:36. Watch a Sony Betamax sales training video from 1977, complete with salesmen role playing.

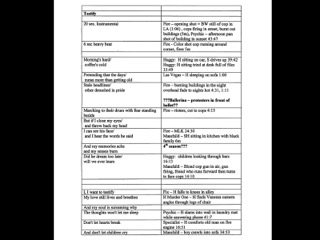

These costs were, however, for the average VCR. Video-editing VCRs remained expensive. In 1993, Sandy Herrold wrote in the vidding letterzine Rainbow Noise:

“Help! I am looking for an editing machine under $600. I want one that will let me hear what I am doing as I am inserting. I’ve looked at a couple of Sonys (though I don’t have the model numbers): one approx. $600, but although it has a wheel on the remote, it doesn’t seem to be a true jog shuttle. (Of course, the next one up ($1000+) has every feature I’ll ever need . . . ) I also looked at a Mitsubishi HS U57. It has a jog shuttle, and a double flying erase head; it’s a little cheaper than the Sony at $525, but I’ve been warned that Mitsubishis start leaving rainbows on your edits 6 months after you buy them. Any truth to this? Anyone had any (bad/good) luck with them? Other recommendations happily accepted.”

Source: Sandy Herrold, Rainbow Noise #1 (March 1993)

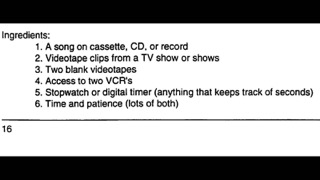

The VCR recommendations prepared by the editor of that letterzine could not find a VCR with all of Sandy’s features for that price (see table). This means a typical vidder in 1993 would have had to shell out $1000 (today’s dollars) for an editing VCR or pay over $1600 for the full-featured VCR. And it took two VCRs to make a fanvid! Often the only source of a second VCR was to borrow one from another fan or to attend a convention “duping” room.

“We will try to have set up both a VTR and a Beta machine in the Video Room for cloning purposes. Head Techie Randy Kaempen is in charge; please contact him if you wish to clone tapes.” Source: Zebracon #2 Program Guide 1980

The convention VCR was usually donated by an attendee and saw heavy use and sometimes damage.

“We desperately need a second Beta machine to use in the Video Room, because the one we’ve used for the last two years isn’t up to the strain of non-stop use. Is there anyone out there who’d be willing to bring their machine to use alternately with ours - so that neither VTR would run more than 4 hours at a stretch? There will be a Security guard in the Video Room 24 hours a day, so you need have no worries there!” Source: Zebracon #3 Progress Report (1981)

The security guard mention in the “VTR Wanted” ad was crucial. Because VCRs were so expensive, there was always a risk they could be stolen.

From a 2012 interview with Kandy Fong and Marnie:

“Marnie S: The very first IDICon [in 1984], each of us brought our VCR to the con. In fact, we brought them in the day before. And unfortunately, we had help from the staff. We put them all in the room. The next morning they had been stolen. In fact, most of the equipment had been stolen. And that all came off of our insur— our own pockets. My brand-new Beta! The best Beta I ever had. Was stolen. So that meant we had to scramble for second back-ups, so the quality and the number was not there. But [in spite of that, at these conventions there] was always something which was brand new. People could sign up for slots, to copy or watch tapes. And there were people in that room round the clock for the entire range of the convention.

KF: Back when you’re young, you go, “Oh, boy, I got the room from four to six a.m.” Source: Media Fandom Oral History Project Interview with Kandy Fong and Marnie (2012)

At the Escapade convention in 1993:

“Kandy also had a huge duping room set up; she was doing l-to-4 Wiseguy all weekend (a fandom that has been really held back by a lack of good tapes; strangely, considering how recent the show is), and allowing two other 1-to-l duping stations to be filled on a sign-up basis all weekend. She had MVD’s’s vids in varying quality, con compilations, and a lot of eps, including new PAL professionally released Pros, that look pretty darn good. The clip quality of Pros songtapes should start to climb soon.” Source: Sandy Herrold, Rainbow Noise #1 (March 1993)

Moving Pictures - Now With Sound!

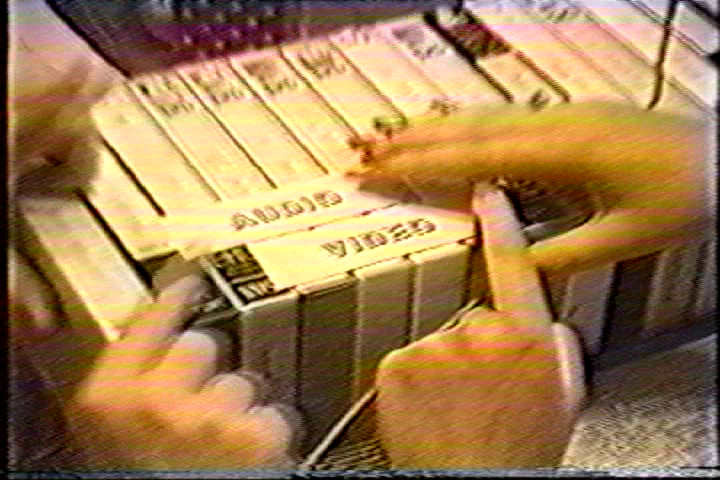

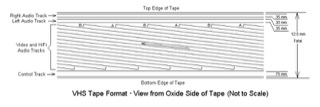

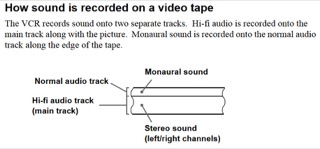

There were still more technical hurdles to overcome: fans could record TV shows off the air and make copies, but they could not replace the TV audio or soundtrack with music. That is, until manufacturers began including the “Audio Dub” feature.

“On nearly all recording VTRs, new sound can be added or DUBBED after the initial recording without erasing the picture. However, the original sound is erased on that portion of the recording where the new sound is added.” Source: The Video Guide by Charles Bensinger (c) 1981

This was possible because while the audio was stored in two locations on the videotape, the video was stored in only one location. It meant that the one audio section that was stored separately could be replaced without overwriting the video.

When the edited (or dubbed) tape was played back, on these later VCRs, the playback sound had to be set to “Mono”. Otherwise, the original audio would play, not the song music. A VCR could be set to play only the new mono track, but if a fan forgot to make the switch, they might get something like this:

An example audio “dubbing”. The first series of clips are taken from the TV show Starsky & Hutch that have been edited together to make a songvid. In these original clips, you can hear snippets of the original dialogue and some of the TV soundtrack. The second series of clips has the new music inserted over the clips. The combination of edited video clips and new audio music track = a fanvid.

Vid: “Don’t Give Up On Us Baby” by Stacy Doyle (Starsky & Hutch) (1990s)

Luckily, these first VCRs were easier to play back because they replaced all the original audio. But these early experiments carried their own set of problems. While the audio could be replaced, editing the video could cause video distortion. This meant that only single long scenes could be used with the audio being supplied from a video cassette player that was connected to the VCR’s “audio in” inputs.

“Diana reports that in the summer of 1980, her friend Kendra H returned home from Greece. Diana lugged her 40 pound RCA VHS machine over to Kendra’s house. Kendra had a Magnavox VHS, and a reel to reel audio tape player. Diana had been wondering what the ‘audio dub’ button on her machine was for. Since they had some of the last season of Starsky & Hutch on a video cassette, they paused a picture on one machine, started the song playing, and hit record on the second machine. …..The vidders decided they wanted action!! But, Diana and Kendra found that if they recorded one scene and then try to record another one after it, they got several seconds of static, unstable images, and music interruption. Their solution was to find one long scene and add music. … “ Source: Morgan Dawn, History of Vidding: 1980-1984, PDF of panel notes presented at Vividcon 2008.

An example of a “single scene vid” is a moment from Starsky & Hutch where the two main characters are drinking in sorrow after the death of Dave Starsky’s’s girlfriend, Terry. The music selected for the vid was Bette Midler’s “The Rose.” The scene was 3:40 minutes long and its length perfectly matched that of the Midler song.

VCR->VCR Process Flow

Eventually, after making a few vids, Kendra and Diana discovered that if they paused the videotape in the recording VCR before editing, the action scene they edited in afterwards looked fine.

The process grew smoother:

VCR 1 was the playback VCR, where they would locate a specific clip from the Starsky & Hutch episodes that they had recorded off air. VCR 1 was then connected to…

VCR 2 (the recording VCR). This is the VCR where the editing took place. The snippets of TV footage from Starsky & Hutch would be reassembled into a new “storyline”. VCR 2 would be hooked up to a TV to see and hear the edits. And (not shown here), a cassette player would be connected to the audio inputs on VCR 2 to “dub” in the new music. Usually the music was added first before the new clips were inserted so the vidder could match the visuals to the music as they worked.

Editing Challenges

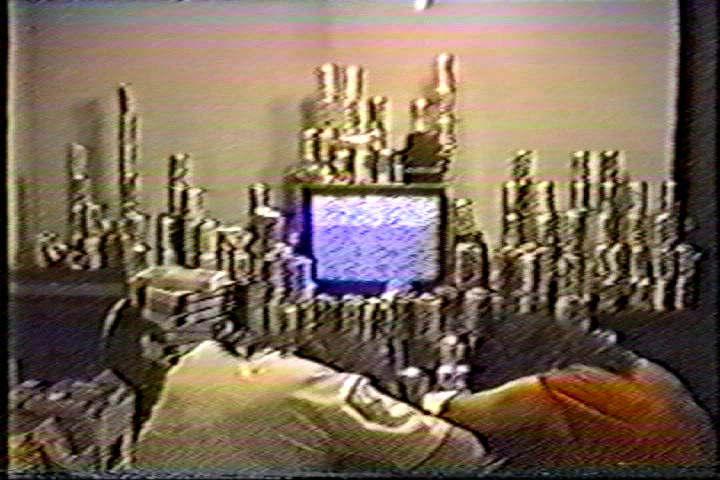

Editing Challenges Part 1: The Fragile Towers of Videotapes and the Rollback Dilemma:

By 1980, fans could obtain source material (record off-air or trade for copies recorded off air), and they could edit the tape and replace the audio with music. But they still faced significant limitations.

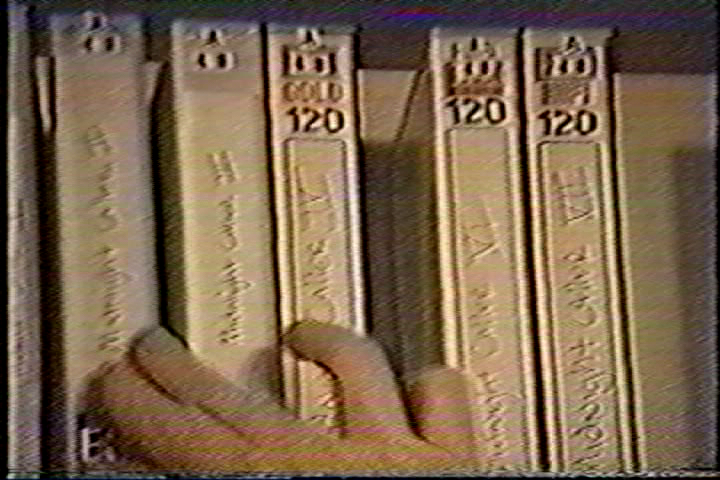

Finding the desired clips required staring at towers of videotapes and fast forwarding through each tape, one by one, to find the right scene. Videotape is fragile and subject to breakage and tangling, and these snarls could render a VCR permanently inoperable. Timing the “edit in” and “edit out” points of a scene was manual. In early days, some VCRs did not even have hour/minute counters to show you how far you had advanced into the tape. Fans used stopwatches to give them the information they needed.

Once a fan had queued up the tape on recording VCR 2, they then queued up the scene on playback VCR 1 and had to manually hit play. Then, with a finger poised over the record button on VCR 2, the vidder had to rely on hand-eye coordination and a sense of timing to hit the record button. It could take up to a dozen tries to insert a single clip correctly. And there was no undo button - all edits were live and irreversible. Another additional stress: each time a fan hit play and record, this compromised the videotape further and further, risking it warping and warbling. Each edit was an exercise in breathless fear, frustration, and hopeful anticipation.

Even non-vidding fans ended up stressing their videotapes beyond endurance by watching and re-watching their favorite scenes. As one vidder wrote in 1993:

“It is possible to love a tape to death. Recently, I borrowed a series from another fan, and I can tell where every one of her favorite scenes is located. Every time she paused the tape - backed it up - paused the tape - replayed it (sometimes in slow motion), the tape stretched a little bit. Now her favorite scenes are bracketed with wavy pictures and rolling images.”

Source: Kandy Fong, Rainbow Noise #2 (June 1993).

Some vidders were better at this timing than others. Familiarity with the quirks of the machine was also essential. Each VCR had a “rollback” that was unique. Rollback is when the drum head of the VCR that reads the videotape rewinds the tape slightly to “grab” enough tape to start recording. In doing so, it erases first few seconds of the previous scene. The rollback could be as few as two seconds or as many as seven seconds of tape. Or there could be no rollback at all. Having a VCR with consistent rollback was crucial. As Morgan Dawn explained in the mid-1990s: “Vidding on someone else’s VCR was like having sex with someone’s else husband. You know all the right moves, but your timing is way off.” Source: Morgan Dawn’s personal notes, used with permission.

A chewed-up videotape, every vidder’s nightmare.

“VCR tape rollback may cause you to lose part of your previous shot if you fail to start the recorder in the proper place for the next shot.”

In 1986 one woman wrote:

We’ve been making S&S (and S/S) songtapes—but before y’all rush off letters to me asking for copies—gasp. Remember my niece, the one who just got Simonized? The one who sits up all night watching my tapes as I sleep, so that I was worried that she’d wear the machines and/or the tapes out? Well, I got home from work yesterday to find a tape stuck in my machine. Not just any tape mind you, but a tape of all the new S&S episodes I’d just cloned and hadn’t watched that closely yet. GAH! Dead niece! Sick VCR! No more songtapes! AAAARGH! I’d put an ill VCR and a stuck tape right up there with a major death in the family. //double tragedy, what with the untimely demise of your niece, and all….//” Source: Simon & Simon Investigations #2, (Sept. 1986)

Editing Challenges Part 2: Analog Video &Linear Editing: Two-Dimensional Living:

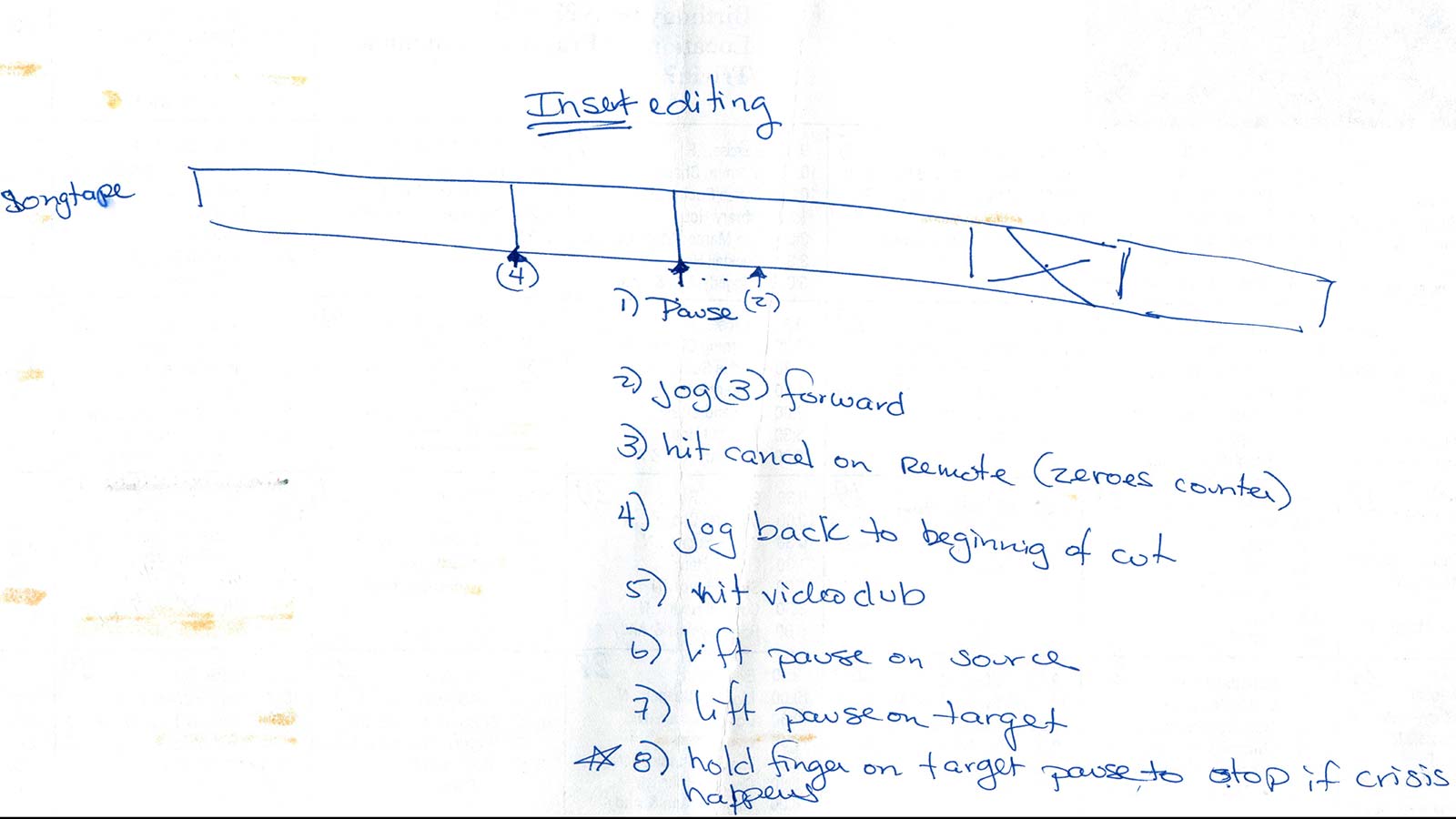

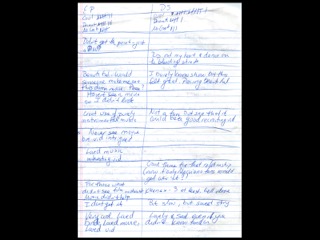

Another “feature” of analog vidding is that a vid has to be made in order, from start to finish. While a fan could theoretically insert a new clip in the middle of a vid, they ran into the problem of erasing the following clip if they did not hit the “pause” button while recording. This is why early analog vidders created storyboards and planned out their vids ahead of time.

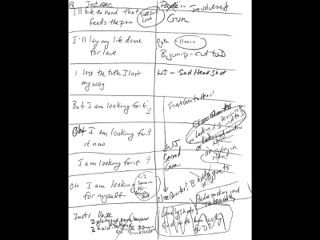

In 1986, Mary Suskind Lansing wrote an essay about the mechanics of fanvids for the Star Trek fanzine, Consort #2. She explained the design process of a fanvid:

Have a written set of lyrics of the song, ideally written only on the left half of the page to leave the right half available for notes. Give yourself at least a few hours over showers and driving to think about the song to see if there are any natural patterns which will lend the song to becoming something more than just a composite of random video shots.

Source: Mary Suskind Lansing, Making Your Own Song Tapes from Consort #2 (Dec. 1986)

The early storyboards were handwritten or typed up on typewriters. In later years, word-processing made the process of listing possible scenes much easier. Stanzas would be assigned an over-arching meaning or theme, and the vidder listed images that seemed to match the themes. The location of the scene on the source tape would also be noted. See the slideshow for storyboard examples.

Not all vidders used storyboards, however. With the introduction of more advanced VCR editing tools in the 1990s, some vidders such as the Media Cannibals dropped them altogether. As one of the members of this vidding collective, Rache, explained: We didn’t use stop watches or storyboard out a vid; we did it on the fly with insert edits combined with flying eraseheads, listening to the music and Sandy’s amazing eye-hand coordination.

Source: Rache’s personal notes, used with permission.

Because these early vidders did not have access to dissolves, transitions or any other effects, they relied on existing scene changes to create motion in a vid. Also, because the fan edits were made manually and VCRs had rollback, tight edits or short clips were difficult to manage. This may be one of the reasons that early fanvids relied heavily on the song’s lyrics to make the point and often ignored what was taking place musically:

Mary Suskind Lansing explained:

The most ideal situation… is to have the video actually show scenes which are consonant with the meaning of the story told by the song. In the song “Home Again” by Carole King, the words can be nicely carried by a set of videos showing one of our heroes in a difficult situation from which they would ideally like to be removed, for example, Spock on the Galileo Seven, trying to return to the Enterprise.”

Source: Mary Suskind Lansing, “Making Your Own Song Tapes,” from Consort #2 (Dec. 1986)

By focusing on the lyrics, the vidder need to make one or two edits per stanza.

To the modern ear and eye some of these older vids can come across as literal, full of talking heads and static shots. However, keep in mind that to this new fanvid audience, the act of simultaneously interpreting both images and lyrics was unfamiliar:

Think all the time about the fact that you are working in a very different medium. With a book, you can always go back and check what you just read. With a song tape, the music and video pass through your mind and you can’t go back to check. This means that some levels of subtlety will never be visible to your audience.”

Source: Mary Suskind Lansing, “Making Your Own Song Tapes,” from Consort #2 (Dec. 1986)

Others cautioned against literalism or simple retelling the same story as depicted in the movie or the TV show.

Even though you’ve planned to simply illustrate a song with your favorite characters, you will probably find yourself revealing something about the character or making a point here or there along the way. Go with it – you have something to say. Ideally, each video should be a mini-movie with a beginning, middle and end. Your opening image should be very strong, should grab the viewer’s eye to pull her into the song. The final image should somehow signify a closing, and leave a strong impression as well. Besides having something to say, ideally a song tape should make over the original material – both the audio recording and the video source material – into something new. Strive to learn to manipulate and transform your material instead of just letting unedited video run past an entire verse of a song, or simply re-telling an episode. Source: Mary Schmidt, Making Fannish Music Videos (3rd revision, 1997)

This is not to say that all early vidders lacked the understanding of complex vid design or story telling. It was that they lacked the tools. In her 1986 essay, Mary Suskind Lansing explained the concept of visual story bracketing: A simple, but effective, idea is to use visual brackets at the beginning and end of the song to set the meaning of the song. This is most effective if you can carry the same brackets into the middle of the song as well. A song with a refrain allows you to use the refrain to carry this bracket. For example, the song “Slipsliding Away” by Simon and Garfunkel can take the theme of the uneasy relationship between Spock and Sarek. By breaking the refusion scene on Vulcan, from beginning to end, into pieces and using them during the refrains, the entire song has a greater visual consistency.

Source: Mary Suskind Lansing, “Making Your Own Song Tapes,” from Consort #2 (Dec. 1986)

Editing Challenges Part 3: Show Me The Good Stuff: Video Tape Quality:

Even though VCRs were available to US consumers by 1975, the main source of video came from off-air recordings. In 1977, a company called Magnetic Video acquired license rights to 50 of Twentieth Century Fox’s movies. A single movie sold for $80 each, or around $300 in today’s dollars.

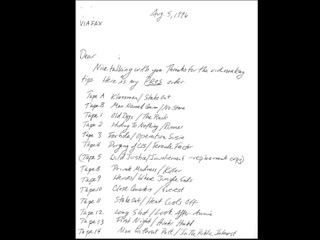

But the consumer sale of TVs series tapes lagged, and it was not until the mid-to-late 1980s that TV episodes were available for purchase. Also, series in syndication were not carried in all markets in the US, episodes were often not aired in order, episodes were dropped, and many were edited down for commercials. Until that time, fans had to make do with off-air recordings. A fan who had uncut episodes of a TV show like Star Trek, Man from U.N.C.L.E., or Starsky & Hutch was considered the pot of gold at the end of the videotape rainbow. This meant that there was a there was a robust fan-to-fan trading network.

The next subject a vidder needed to be knowledgeable about when buying or trading tapes was videotape quality. This was because when each copy of a videotape was made, there was signal loss due to magnetic tape’s inability to transmit data and imperfections in electronic circuitry in reading that data; colors bled, clarity was reduced, and grain increased. This was called generation loss. Knowing whether a copy of a VCR tape was “1st Gen” (copied only once from the master video tape) or “2nd Gen” (copy of a copy) was important, because by the very act of editing a video, and then making copies to share, took up two “generations”. By the time fans reached “5th gen” or “6th gen” copies, the video was often so badly degraded faces were blobs and sound was warbling and tinny.

Example of “generation loss” when copying from VHS tapes. Most copies of British TV shows like “The Professionals” were 4th gen or worse. Fans would spend hours arguing over small details or the color of their favorite characters eyes. Most US fen had to take “The Professionals” fanfic as canon because the video was too degraded. That is assuming they could even find copies of the show to watch. Source: The Professionals, A Fandom of Exacting Standards (Fanlore)

In 1996, one vidder posted the following notice in an adzine:

ATTN SONGTAPE FANS!! Please note that all music videos with piano logo titles are done by ‘JAM’, including S&H vids & a multi media called ‘Move This’. Nth gen copies are being passed around (which are barely watchable) with no idea who did them. Please, do not copy! This is bootlegging my work!! If interested in copies, SASE ONLY (no after receiving the tapes! Fandoms include: B7, QL, B/D; S&H, Multimedia and many others.”

Source: On the Double #34 (Jan. 1996)

Another factor that impacted videotape quality was recording speed. Videotapes could be recorded at:

- “SP” (Standard Play) with 2 hours of video per tape

- “LP” (Long Play) with 4 hours of video per tape

- “EP” (Extended Play) with 6 hours of video per tape

SP videotape recordings were in high demand with vidders because they offered better video resolution. Non-vidders would often record at LP or EP speed in order to save money and shelf space. To give an idea of the economic savings: in 1987, the cost of a single blank video tape in today’s dollars was $10. This meant that a single season of Miami Vice recorded off-air in SP would cost a fan around $122 but only $40 if it were recorded at EP speed.

Of course, there were added complications! TV shows that aired in Europe were recorded in a different format, called PAL. PAL tapes could not play in US machines (or vice versa).

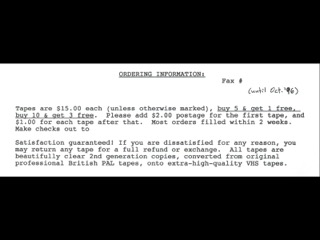

An additional challenge: because there was little commercial sales of British TV shows in the US, only a few British shows were ever aired in the US. This meant if one was a fan of Doctor Who, The Professionals or Blake’s 7, one had to hope your local public TV would buy the rights to the show and air them so you could record them. In the 1990s, this meant there was a market for fans selling higher quality copies of these British shows to US vidders, at a whopping $15 per tape ($23 per tape in today’s dollars).

Editing Challenges Part 4: Macrovision Was A Dirty Word:

With off-air recording deemed legal, the entertainment industry shifted their focus to the sale of movie videotapes. By the mid-1980s, video rental stores emerged, and rather than embracing the new consumer model, the studios once again miss-stepped, this time suing to stop videocassette rentals. When this tactic failed, the studios dramatically increased the prices of movies on VCR for home purchase.

“The studios then countered by raising the prices of the movies and by 1983, some titles were up to $79.99 SRP [$190 per tape in 2016 dollars]. The rising prices also meant an increase in illegal copying.” Source: The History Of The VHS Movie Industry

Once again, the studios attempted to solve a problem that they had partially self-created. In 1982, they introduced an anti-copying technology known as “Macrovision.” During playback to another recording VCR, Macrovision would turn the video signal fuzzy and the brightness and color would fade in and out. While the casual consumer was prevented from making copies, professional pirates soon found a way to circumvent the wavering signal.

Videotape with Macrovision. Image Source: Wikipedia. “The way the copy protection signal works is interesting. It’s not that the second VCR “knows” that the video signal is coming from a video tape. It’s that the signal coming from the original video tape contains a special type of noise that the TV set doesn’t notice but a VCR cannot handle. This noise signal confuses a component, known as an automatic gain control (AGC) circuit, in the VCR, and the confused AGC records the signal incorrectly.” Source: How does copy protection on a video tape work?

Since most fans obtained their sources off-air or from other fans, Macrovision was not a problem for the first few years. However, vidders who wanted to use cinema sources wrestled with various “video clarifying” devices designed to strip away the encryption ‘noise’ and generate a clear unprotected signal. If a fan didn’t have access to the devices, the alternatives were few:

“If you can hang on, the movie may later come out in a sell-thru version that isn’t encoded. (Perhaps you can borrow a friend’s copy, or another video fannish helper may know for sure.) Or wait until it hits pay-per-view (which usually happens around the time it hits video), HBO or Showtime, or other TV, and get a first gen from that. (Even if it’s chopped to ribbons on network TV, you might still get useable footage from what’s left.)” Source: Mary Schmidt, Making Fannish Music Videos (3rd revision, 1997)

When a TV series eventually became available for commercial resale, those vidders relying on TV footage faced the same limited choices. It is not surprising that when the third season of the TV show Highlander was released without copy-guard in 1997, vidders on the Virgule-L mailing list rejoiced:

“The Highlander professional tapes are NOT copy protected. I was so sure they would be. We just got season 3 and taped Methos last night (don’t want to wear out the original) and there wasn’t any problem!” Source: Stacy D’s post to the Virgule-L mailing list dated Jan 16, 1997, quoted with permission.

However, even when the signals were stripped and copied over to an unprotected tape, Macrovison could still reappear in the next copy, lingering like a dormant virus. This was most likely because the signal stripping devices could not always completely remove the Macrovision and stray signals “leaked” through to be copied onto the next tape. This is one reason why “Data’s Dream”, a popular 1990s fanvid was remastered in 2004; the vidders could not reliably remove the Macrovision from the original tape to create additional copies.

Editing Challenges Part 5: Rainbow Noise, Flying Erase Heads, Jog Shuttles and Dirty Frames:

Another technological challenge in early vidding was the dreaded “Rainbow Noise” which could only be defeated by its arch-rival “The Flying Erase Head”.

So what is a flying erase head? Contrary to its name, it isn’t something out of David Lynch’s nightmares, it’s a moving head that erases the partial frames left by editing, for a clean, flashless cut. Without a flying erase head, the rainbow noise between cuts is very annoying, especially in later generations (copies). I don’t recommend working without this feature.”

Source: Rainbow Noise #1, March 1993

But alas, the life cycle of a flying erase head was limited, and most vidding VCRs buckled under the pressure of a vidder’s atypical heavy use:

Flying erase heads - though necessary, these are a pain in the butt. As far as I know, all erase heads in home machines deteriorate somewhat after a few months of hard use. And let’s face it, we song vid makers give a VCR harder use than manufacturers count on. Hint: to check how cleanly your erase head is working, check the top of the screen for little flashes of black or white at the cuts. This garbage makes for a more jarring cut, but isn’t uncommon (you can always lay in the cut again, if it’s too noticeable, since the problem is usually intermittent). But if you start getting big, flashy rainbows, the head has stopped working, and should be serviced For reasons like this, do get an extended warranty instead of 90 days!”

Source: Rainbow Noise #1, March 1993.

An example of “rainbow noise” which can be seen over the right side of the actor’s face. VCRs with a flying erase head eliminated the rainbow noise that came from inserting new video clips. TV Source: Simon & Simon

Another important feature to have in a 1990-era VCR vidding was a “jog shuttle.” Situated on either the VCR remote or the front of the VCR (or both), the jog shuttle allowed the vidder to scroll back and forth on the videotape frame by frame from. This allowed one to insert a new clip more precisely. It also allowed video editors the ability to edit out “dirty frames” - the leftover frames from the previous clip that remained after inserting new clips. As Mary Schmidt explained: I use my jog shuttle to pause the editing VCR on the very first frame of the clip I’m re-doing. Try this and see if your edit is clean. If you get a frame of the old clip (do the replay in frame-by-frame) you’ll have to pause the editing VCR on the last frame of the previous clip (or the last frame of black space if it’s your first clip). Leaving in those stray frames will cause a jump instead of a clean edit. A jog shuttle makes this part really easy.

Source: Mary Schmidt, Making Fannish Music Videos (3rd revision, 1997)

A stack of late model Panasonic SVHS VCRs with jog shuttle “dials” on the right. Source: What VCR’s DO YOU OWN – AVS Forum (2007) “Jog shuttle: a control on some newer VCRs, consisting of an outer ring and an inner dial, that allows you to perform several special effects including searching forwards OR backwards at various speeds…. frame-by-frame….. On the editing machine this makes it ridiculously easy to find the exact frame to begin recording a video clip when you video dub.” Source: Mary Schmidt, “Making Fannish Music Videos “ (3rd revision, 1997)

So what did an ideal VCR editing setup look like? A vidder in 1993 asked:

“What do the rest of you use, and what do you like and dislike about it? I do my viewing and taping with an RCA VR 740 (Panasonic-made, ‘91, $800, SVHS), which has the best picture I’ve ever seen unless you go to studio quality. Though it has edit features, including a jog/shuttle, I don’t use it for dubbing because like many ‘90-92 models, there is a large, inconsistent rollback (37-45 frames! No precision is possible with that variation—beats missed all over the place). During vidding, it’s my source.

My editing machine is [Vidder GF’s] (non-Panasonic) RCA VR 685 (‘91, $599), which has a very precise Jog/shuttle and consistent 4 frame rollback. Though the picture is grainy compared to the VR 740, it’s a dream to edit with. BUT-I’ve had to learn to get along without hearing the music as I work. This means I must edit in order, since if you can’t hear the music, you must run a little over. For me, this was a little disorienting at first, but no major problem, since I have always preferred working in order, for a specific reason. True, It means I must have the main drift of the vid clear In my mind before I edit. But whether or not you can hear the musk, I strongly recommend working in order, since no one’s finger is frame-accurate.” Source: Rainbow Noise #1 (March 1993)

Editing Challenges Part 6: Just The Straight Cuts Ma’am, Nothing Fancy:

Because VCR editing used existing analog source (videotape), there was no ability to materially alter the source. This meant vidders could not add transitions, dissolves or cross-fades beyond those that were already placed into the original video. Fans would make special note of these existing effects because by re-purposing them, they allowed a vidder to vary the flow of their vid. Color correction, lightening or darkening video, speeding up or slowing down clips - all of these tools remained out of reach for the majority of analog vidders who had no access to special high end commercial editing equipment.

Even the ability to make fast paced edits was challenging for many vidders. Starting and stopping both the playback and recording VCR required quick reflexes and perfect timing and even with the nimblest editor, there was always a lag due to the mechanical parts of the VCR.

For this reason, many of the fanvids of the 1980s favored long clips that could last an entire stanza. There were exceptions of course: in the late 1980s and early 1990s the vidding team, Shadow Songs, was well known for their rapid-fire edits that were perfectly timed to the beat.

In the 1990s, two vidding groups, the Media Cannibals and JKL spent considerable time focusing on timing both the edits as well as the arranging flow of their scenes to hit the beats and key musical stress points.

With more finely tuned VCR equipment, vidders could start focusing on what the music beneath the lyrics was doing, turning two dimensional vids into an exercise in multi-dimensional composition.

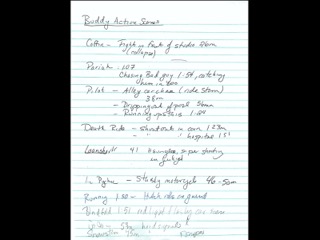

Continental Drift is a Blake’s 7 fanvid edited by Tashery, a member of Shadow Songs. The vid is a character study of Avon and was highly regarded for the timing of its fast edits and cuts, particularly in the last 30 seconds, something that was difficult to achieve in analog VCR vidding. In 2009, the vid was shown at Vividcon’s “Envelope Pushers of the Past” vid show. The vid was also discussed that year at Vividcon’s “History of Vidding 1985-1990”: “What made this vid stand out was the music choice, very unique selection for a fanvid for its time. She treated the vid like a story by using her edits to build to a narrative climax.” Source: Fanlore, Continental Drift

Editing Challenges Part 7: Audio Editing, What’s That?

Likewise, editing the audio source was difficult. Cassette tape editing decks could only remove music. Adding music or rearranging stanzas was jarring and obvious. Like video, there was no ability to use dissolves or fades and layering the original audio soundtrack over the music or changing volume and pitch was not possible. CDs could not be edited, so vidders would often copy the music onto a cassette deck recorder, manually edit it there, and then feed that version back into the VCR. Each copy resulted in a reduction of audio quality. The audio edits were hard and abrupt and usually unpleasing.

In the mid 1990s, when Media Cannibals used a Billy Bragg song “Tender Comrade” they struggled to find a way to remove the long silent pauses between lyrics. The pauses would, they felt, slowed down and interrupted the flow of the vid. The vidders ran the CD into an audiocassette tape deck and manually started and stopped the tape to edit out the silence. Because cassette deck counters were not precise and because there was a hard limit on the time it took to stop and start the tape, another a second person had to manually clap out beats so they could approximately edit out the same amount of dead space from each stanza. They also edited the song to remove several lines. This means that the video’s music is over forty seconds shorter than the original.

Another technique vidders used was to play the CD directly onto the videotape, using “waste footage” as the video base. This base would be replaced by TV and movie clips later. Rache from Media Cannibals remembers: I know that in our Pros video “You’re My Best Friend”, the lyrics mention “girl”. Because the video is about two men, Sandy deliberately lowered the volume at the section while we were recording it onto the video tape. After the word she raised the volume for the rest of the song. We also cut out entire verses, using Sandy’s musical ear and her skilled eye to stop and start the videotape as the music was fed into the VCR. That’s what we did with our Highlander vid “Us”. In order to distract the viewer from the bad mesh on the audio edit, we put in what was then considered ‘fast cuts’. You can see those edits around 2:09 in the vid. It seemed to work great at the time, but of course now those edits are not considered fast at all.

Source: Rache’s personal notes, used with permission.

Another notable exception from the 1990s was Shadow Song’s Wisgeuy vid “Nights in White Satin” which used Moody Blue’s music as the backdrop to a dramatic scene between two male characters, with the actors speaking their lines over the music playing in the background. Through careful editing, the vidders were able to graft the TV scene with the original dialog and music onto the studio-recorded version of the song. This was then matched with different clips from the entire series.

Vidshows

The Rise of Convention Vidshows - Part 1: Let’s All Go To The Movies:

While the first slideshow vids were shown at Star Trek conventions, the first “moving picture” fanvids were shown in in living rooms and hotel suites, to small groups of people. In 1980, when Kendra Hunter and Diana Barbour finished creating their Starsky & Hutch vids, they knew there was only one place they could show them: a fan-run Starsky & Hutch convention in Chicago that year called ZebraCon. So, in the fall of 1980, Kendra, Diana, and their 40-pound VCR left California and went on the road.

“Kendra and Diana found a friend with nice handwriting, and used a camera for the credits. [Other friends] helped them with source material and song choices. But, none of their friends knew exactly what Kendra and Diana were doing. They made 20 songs videos by Z-Con 2 ….They carefully put the gen on one tape and the ‘underground’ slash on a different tape. The night before the con, Diana decide that they needed more credits…..Diana and Kendra spent the con inviting people into their room to share their crack. i.e. vids. They blew everyone away - no one had seen anything like that. They spent the whole con showing their work over and over, and explaining how they did it. The next year, 1981, sixteen people showed up with vids they had made, and they were inviting people into their rooms.” Source: History of Vidding: 1980-1984 (PDF of panel notes presented at Vividcon 2008)

The song tapes at ZebraCon were a big hit and were the subject of letters of comment to the fan-published letterzine, S and H”: “Thanks, Diana, for playing your VTR S&H song tapes over and ever and over … and over, it was greatly appreciated

wrote one fan after the convention. Source: S and H #16 (Dec. 1980)

The next year, Kendra submitted a notice to the same Starsky & Hutch letterzine in Oct 1981: I hope all of you are as excited about Z-Con III as Diana and I are. This gathering of fans has the potential of being the most exciting events of our time… Diana and I will be bringing our song tape. I will be shown in our room, 201. The schedule will be posted on the door. We are looking forward to seeing what others have done in this area. The grapevine says that new and exciting adventures are being taking into this medium of artistic expression.

Source: S and H #26 (Oct. 1981)

The fandom enthusiasm for songvids did not go unnoticed, and after Zebracon III, the convention organizers asked: Is it worth continuing the video room [at Zcon 4]? Should we have a special time for people to watch song tapes?

Source: S and H #28 (Dec. 1981)

Eventually, the crowd grew too large for the hotel rooms and convention “vidshows” were created to accommodate the growing number of fans who wanted to see the vids.

Convention Vidshows - Part 2: Let’s All Do The Timeshift Again: The Sony Supreme Court Case:

Large group showings of fanvids were not immediately embraced. Part of this had to do with the fluid legal status of early video recording technology. In 1976, the TV and movie industry sued Sony, the manufacturer of the Betamax VCR, alleging that because Sony was building a device that could be used for copyright infringement, arguing that therefore Sony should be liable for any infringement committed by VCR consumers. By 1978, the court had ruled in favor of Sony, but a few years later, the appeals court reversed and ruled in favor the movie industry. The result was the case being sent up to the US Supreme Court. Source: Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc.

This legal wrangling led ZebraCon to put the brakes on vidshows. In 1982, worries over the legality of videotaping and showing videos led ZebraCon to announce:

“Due to the ambiguity of the current legal situation concerning videotapes, ZEBRACON is not programming any video presentation, and therefore, membership to ZEBRACON in no way constitutes payment for the viewing of video programs. We will, however, provide space for videophiles to get together for private showings of their favorite tapes….A sign-up sheet will be posted on the door, and if you have any tape you’d like to show - and a machine to use - you can choose a time and list it on the board. We cannot provide video machines or tapes this year, sorry” Source: ZebraCon #4 Progress Report #1-3 (1982).

Fans’ reluctance continued through 1984:

“There is no video room, as such, again this year. We stopped having one be cause of all the legal confusion and ambiguities; last time we provided a room for people who wanted to bring their own machines and tapes, but everyone just showed tapes in their rooms and it was wasted. So, this time you are totally on your own as far as video goes. There will be a message board set up at Registration, and anyone wishing to show tapes in her room could put an announcement up there.” Source: ZebraCon #5 Progress Report #1 (1984)

In December 1984, the US Supreme ruled that “time-shifting” (recording a free TV show for later viewing) was lawful “fair use” and was not copyright infringement. Source: Supreme Court Rules Home Use of VCRS Okay

Earlier that year, MediaWestCon, another fan-run media fandom convention, held its first “Film/Video Competition.” Also in 1984, the second annual Dark Shadows Festival in Newark, NJ in July sponsored its own event: A music video featuring relevant scenes from “Dark Shadows” set to such popular tunes: “Who Can It Be Now?”, “You Can Do Magic·’, and “Memory (Theme From “Cats”)”, [The songtape] was prepared by Mary Overstreet, Carol Maschke and Kathleen Reynolds. Their tape was very entertaining and much enjoyed by all.

Source: The World of Dark Shadows #38

By 1986, the ZebraCon video room was back showing Starsky & Hutch and The Professionals songtapes, and in 1989, the con began hosting a Friday Night Song Tape Contest.

Convention Vidshows - Part 3: Structuring A Vidshow:

Legal issues aside, the technical hurdles of these early vidshows were formidable. Larger venues dwarfed the relatively small 19-inch TV screens. Sound quality was poor with only the built-in TV speakers. The TV often had to be mounted on a table or tall stand. Seating was limited to ballroom chairs and those in the back had to peer between audience heads. Convention attendees would wait an hour in advance of the vidshow to secure a “good” seat.

Additional technical challenges were created when the two competing VCR formats, Betamax and VHS, emerged. Since Betamax was first to market, and was perceived to have better picture quality, many of the early vidders favored that format. Later entrants found themselves at a disadvantage because small fan-run conventions could not afford to host both VCR formats.

From 1986 ZebraCon: A few S&S episodes were shown at the Con, but as they only had Beta machines (boo, hiss, and no VHS), I couldn’t show anybody the stuff I’d brought with me. We’ve been making S&S (and S/S) songtapes.

Source: convention report in Simon and Simon Investigations #2 (July 1986)

Of course, once VHS gained popularity the pendulum shifted against Betamax VCRs. By 1989, the MediaWest*Con vid contest announced they would only be accepting vids on VHS tape.

The audience experience at these early vidshows was often characterized by stops and starts with repetitive sequences of vids stemming from the same TV shows, using the same popular clips. If the convention could obtain both VCR equipment formats, they would show all the Betamax vids first, then disconnect the Betamax VCR from the TV, connect the VHS VCR to the TV, and finally show the VHS vids.

Even after the industry settled on a single format by the 1990s, vidshows remained uneven. Vidders or vidding collectives had to submit their entries on a single tape. When the tape ended, the show would stop to allow the next tape to be inserted into the VCR. Sometimes in order to create a better audience experience, vidshow organizers would copy all the vid entries onto a single tape. This resulted the loss of video and sound quality. While it made the audience happy, it also made some vidders unhappy.

In addition to grouping vids by a single vidder or collective onto single tape, the content of the vids themselves ended up grouped together, in ways that audiences could find boring. A vidder who assembled six Star Trek vids and submitted those six vids, forced the audience to watch one after another. If a fandom was popular, the audience could be overwhelmed with fanvids from the same movie or TV series, with vidders often selecting the same iconic scenes.

[Two of my friends] were really in to Voyager, and had made an hour of Voyager….vids. And their main thing that they were interested in was Paris and B’Elanna, so there was an hour of vids about Paris and B’Elanna. And, you know, that’s fine; I just felt that, for a vid show, that there should be a little bit of variety. This is something actually that California Crew told me, that I apparently still remembered, from their first vid panel that I went to. That there should be a variety of tone, of fast/slow, ballad/funny, you know, just to keep the audience interested. And I was like, ok, well, all right. If I manage to finish the Mystery Science Theater 3000 vid at the con, there will be, we can have half an hour of Paris and B’Elanna, then my vid, then another half hour of Paris and B’Elanna.

It would be better if we could like divide it into thirds….. And of course then when they put them all together they did an hour of Paris and B’Elanna and put my two at the end.

Source: Media Fandom Oral History Project Interview with Judy Chien (2012)

While most early vidshows would take any and all vids, some concoms started imposing limits, both in number of vids submitted, and in content.

By 1991, so many videos were submitted to the MediaWest*Con fan video contest that the concom instituted a fifteen-minute-per-person limit. Vidding collectives could enter fifteen minutes per person in the group. Anything entered over that limit could still be shown at a time other than Friday night and any other “competition” re-runs, but would not be eligible for prizes.

MediaWest*Con was also known as one of the few (possibly only) fan convention to segregate slash fan videos from other video genres. From their 1997 progress report: Due to complaints last year, any “slash” themed videos will be scheduled separately; as such, they cannot be considered for the general fannish video competition; however, “slash” awards will be considered if there are enough entries to compete.

Source: MediaWest*Con progress report (1997).

As of 2017, MediaWest*Con’s policy regarding slash vids was still in place.

Convention Vidshows - Part 4: The Life Of A Lonely Vidder:

Obtaining feedback for fanvids was extremely difficult for these early vidders. Distributing copies of songvids on tape was expensive and time consuming as each tape had to be made individually. Also, each copy that was made put more wear on both the master video tape as well as the VCR.

Vidders were also wary of legal challenges as they were transforming not only images but also music. Vidders rarely advertised their vids, even in fan publications.

Finally, since early vidders often lacked the ability to add credits or title cards to their works, many fans watched vids and had no idea who had created them, something that greatly hindered feedback and conversation.

In spite of these obstacles, fanvids remained popular and convention attendees would track down the creators and beg for copies of their fanvids. Those who could not attend conventions would hear about vids, and then want to see them, often made difficult due to the fact that many vidders used pseudonyms, leaving many fans in the dark regarding whom to write to. To meet this demand, Kandy Fong started creating and selling contapes in the early 1990s. A “contape” was a tape that copied all the vids that had been shown at the convention onto a single tape, which then could be sold, to convention attendees and non-attendees alike.

Still, even with this improved distribution, vidders often had to rely on friends who attended conventions to report back on their vid’s reception. Of course, if vidders attended an event in person, they had the opportunity to be in the audience when the vid was played. And the audiences were not always kind:

One vidder, Flamingo, remembers:

“My first vid was so bad, I showed it at Connexions, very large audience, maybe two hundred, two hundred fifty people… And they laughed at all the wrong places. There was nothing funny about the vid; it was a drama vid, and they laughed all the way through it. It was just a nightmare…. …It got to the point where I could not be in the room when I showed my vids. It just was too difficult, after spending, you know, days and weeks and hours working on this vid, and to have people say, “Oh god, you picked that song?” And I had somebody say that, out loud, as the first few bars of my song started to play…..

..[The] audience can be incredibly rude. And nobody would ever scold them about it, either. It’s like, which is why whenever I do a vidshow, the first thing I say is, you know, “Respect the vidder. Even the worst vid we’re showing has taken dozens and dozens of hours to do, and a tremendous amount of labor. And you’re going to hear the same songs, you’re going to see the same clips; have some respect for the work that it involves.”

Source: Media Fandom Oral History Project Interview with Flamingo (2013)

To be fair, the audience had little time to react to vids in a thoughtful manner. The vids were shown once, live, sometimes over long two-hour blocks. The audience’s response often had nothing to do with the quality of the vid itself. Popular fandoms would be greeted with cheers, less popular or unknown fandoms generated a muted response. If a vidder had selected a popular fandom, the audience might be overwhelmed or bored when the vid finally appeared. Where a fan’s vid was placed in the show could also make a difference. The sound and video could vary for the first few vids as organizers struggled with finicky VCRs that threw off unexpected tracking errors and TV speakers that cut in and out due to the inconsistent quality of thrice copied videotape.

One vidder from the 1990s remembers the watching one of her early vids at a convention:

“I was at Escapade and a few hours before the show, a friend slammed my hand inside a car door. I refused to go to the ER because I really wanted to see my vid live in front of an audience. Luckily nothing was broken, so I sat through the show with my hand buried in a hotel room ice bucket. When my vid came onto the screen I remember Gayle F, an experienced and well respected vidder, reaching out to pat my arm in solidarity and understanding. I was both terrified and excited. Watching my vid and hearing the audience reaction was the biggest rush in my life. It felt like performance art on stage. I was hooked.” Source: Morgan Dawn’s personal recollections, used with permission.

Because fans reactions to fanvids was based on their fanvids was based on their familiarity with and fondness of both the song and the particular TV show, the feedback that vidders did receive was often felt wanting. Vidders lacked the language to communicate with one another and their audience lacked the language to communicate with them.

Borrowing terms from film editing helped, but because vidding pre-dated MTV music videos, fanvids’ shorter clips, lack of dialog and use of music to underscore visuals was not part of the typical moviegoer’s experience.

In the 1990s, as vids obtained better sources and more vidders were able to afford VCRs, a few fans decided to take matters in their own hands. They started hosting panels designed to discuss the content of the vids, stepping away from the purely instructional panels based on the mechanics of how to make a vid with two VCRs.

In 1997, Sandy Herrold and Tashery S held a Sunday morning “Songvid Critique” panels at Escapade, a vidding con. This panel had the description: “An exploration of different elements of media vids, with an emphasis on aesthetics. We’ll look at segments of different songs to see how the images were used in conjunction with the varied rhythms of the music, and to enhance the mood.”

The next year, the Sunday morning panel was billed as a “Music Video Show Review,” using the word “review” for the first time; the panel was held in two parts and was led by Gayle F and Sandy. In 1999, the panel was billed as “Sunday Morning Vid Review” and was led by Jessica aka tzikeh and Sandy. In 2000, it was framed as “Songvid Appreciation 101” which explicitly claimed to be using the vids from the previous night’s show to illustrate these ideas in a vid. In 2001, Sandy and Rache together hosted: “Songvid Appreciation Escapade style”.

Their initial idea for Vid Review was simple: on Sunday morning, after the Saturday evening vidshow, fans would gather to discuss each vid one by one. The focus would be on what fans liked, what fans didn’t like, and why.

Over time, a vocabulary emerged to describe why viewer reactions varied. Through these formal Vid Reviews, the vidding community gained a greater understanding that the vid audience was not only made up of fans from different fandoms, but fans of different types of music, along with fans who watch TV and movies in different ways. It also illustrated that some fans absorb meaning from music and others seek visual meaning. It showed that a fan that was exposed to fanvids for the first time may have difficulty understanding a context-based fanvid (a vid that relies on the content of the clip to underscore its meaning). Fans new to vids might gravitate towards more literal pairings of song lyrics with images (“If the singer says: “My heart is on fire,” there’d better be flames” is how one vidder described it.). Fans who are deeply into one show and have memorized the episodes can pick up subtler nuances and ironic juxtapositions. As Rache explained; some viewers ‘read’ fanvids at the kindergarten level and some read fans vids at a college level.

Other aspects of fanvids came into focus: the difference between a con vid and a living room vid, how the choice of color could influence mood, and how pacing and variation in cuts either build or lose tension. Vidders were advised to pay attention to a song’s “stress points” and to match the action in the vid to those stress points (track either the climactic music or the quieter moments). More and more vidders began talking about “cutting on the beat” which in turn helped viewers understand why a vid worked for them when it did just that. There was greater attention on establishing a POV early on in the vid (when the singer says “I” or “me” the clip should focus on the character who is the POV character or the one telling the story). Changing POV multiple times could be confusing and this could translate into losing viewers.

The Law of the Diminishing Audiences was more openly discussed:

“With every vid, you start with an unlimited potential vidding audience. With every vidding choice you peel away viewers. You decide to do an X-Files vid and you lose 20% of the audience who has never watched X-Files and never will. You then choose to create a Mulder/Scully het vid - whoops, there goes another 25% of your audience who is only there to see slash vids. Now you’re down to 50%. You pick a country western song and suddenly you’re down to the last 5%. And that is before you’ve even made a single edit. Once you understand, as a vidder, that each decision leads you down the path to a different audience, you can understand why this audience didn’t “grok” your vid. Or why that audience began wildly cheering and dancing in the aisles. It is not you. It is not them. It is not the vid. It is the meeting of all three - or, as in some cases, the missing of all three that explains a vid’s overall reception. Source: Morgan Dawn’s personal notes, used with permission, posted to Fanlore.

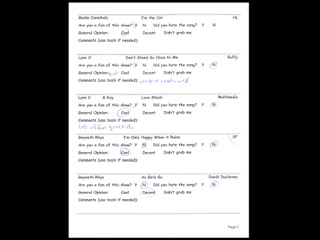

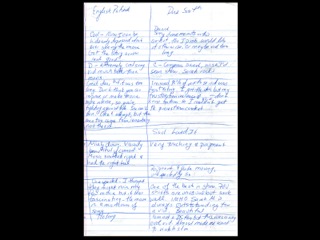

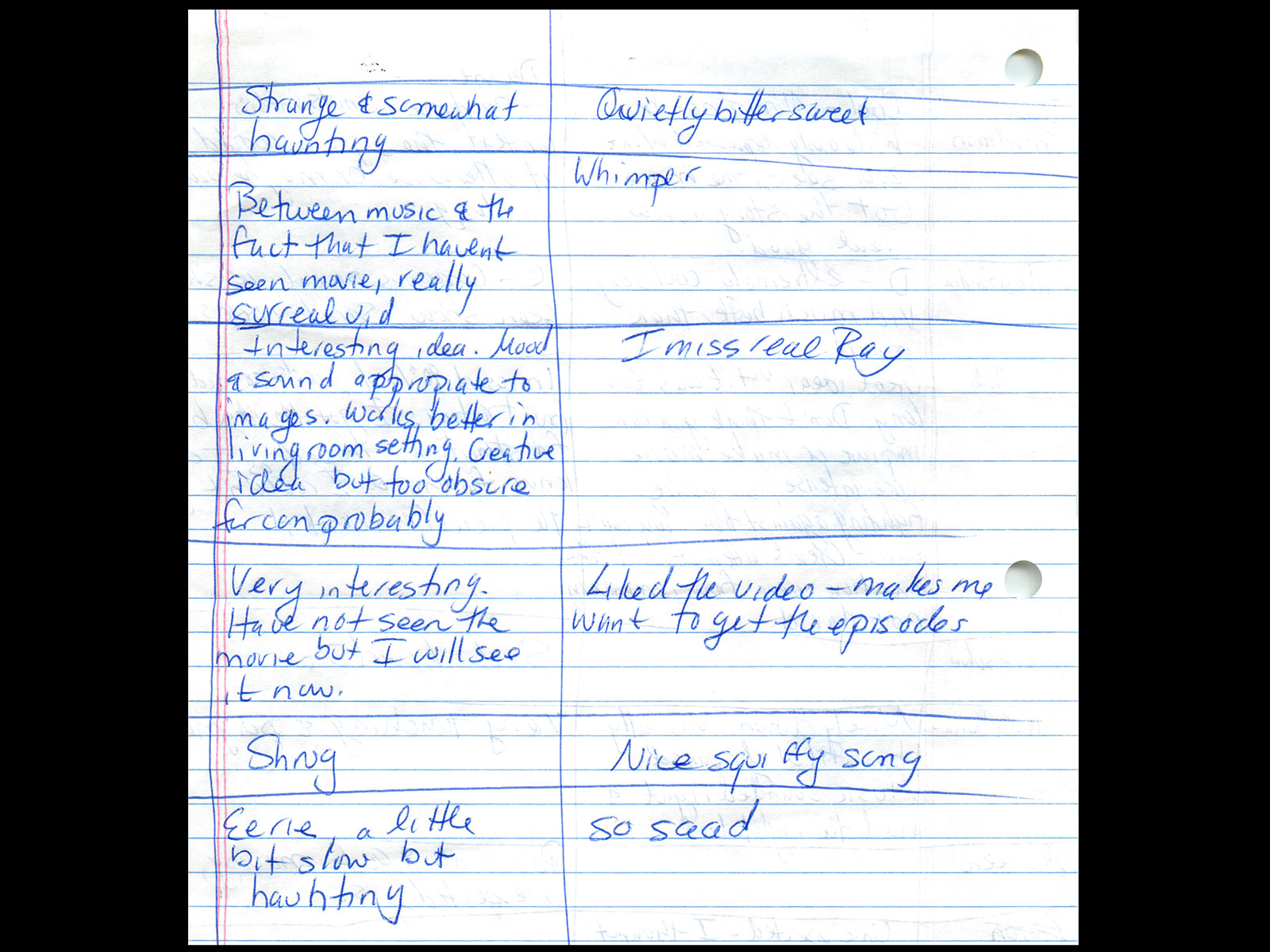

Other experiments followed. In the late 1990s, vid feedback forms were handed out to vidshow attendees at the Escapade and ZebraCon conventions. The comment sheets asked the audience to offer their thoughts on each vid as they watched. The show paused for a short time after each vid to give fans a chance to write down their quick comments. After the vidshow, the forms would then be cut into sections allowing vidders to take their comments home. However, before this happened, vidders would gather around a table containing the forms immediately after the end of the vid to read their feedback (sometimes aloud) and marvel at both the perspicacity and obtuseness of their vid audience. The idea, which originated with Sandy Herrold and Rache was eventually abandoned in the early 2000s. Some vidders felt that the feedback received was often superficial. Some audience members found it too distracting to watch the vids and write feedback in a 4-5 minute span in the dark.

But while the original formal project was discontinued, the conversations and the experiences had furthered interest in the areas of vocabulary and concepts, giving both vid creators and audience members increased appreciation and abilities to talk about vidding with each other.

Cutting Women

Cutting Women - Vidding Collaboration And The Tapestry of Women:

Given the costs of video editing equipment, it is hard to say how many fans were making fanvids in the US in the early 1980s. We do know that shortly after Kendra Hunter and Diana Barbour made their vids, other groups of women began vidding. Two of these collaborations were Three Sisters (Donna Williams, Linda Brandt and Lucy Keifer) and a group made up of Carol Huffman, Terry Martin, and Elaine Hauptman. Between them, they released two more songtapes: one in 1983 called “The Texas Tape” (twenty-three vids) and one a few years later called “Dialogue & Songtape”. Another development in the late-1980s: Kandy Fong bought a Betamax VCR and switched from slideshows to live action video editing.

An informal survey of fanvids made in the VCR era during the 1980s and 1990s on Fanlore shows well over 1200 titles with over 160 vidders. This list is not representative because large conventions like MediaWest*Con failed to track their vidshow entries and sometimes even their own contest winners. Other conventions did not have contests, opting for straight-up vidshows instead. And most of these conventions, like ZebraCon, Eclecticon, Mountain Media Con, Virgule,, Koon-ut-Cali-Con,, and IDICon are no longer operational. If any records were kept, they have been lost to time. Finally, even when the vids themselves have survived, they lack title cards or the names of the contributors.

It was not until the 1990s, when vidders gathered at Escapade that extensive cross-pollination began. Escapade saw the creation of the vid review panel, vid feedback forms, and at those panels and reviews vidders started to develop their own vocabulary about how to construct a fanvid. Between 1992 and 2000, over 50 vidders submitted their fanvids to Escapade. Many of those attendees went on to support the creation of Vividcon, the first fan-run convention devoted solely to the art of “vidding”.

Even without reliable data, it is clear from the info that survives that VCR era vidders were inter-connected and relied on one another extensively. This collaboration - both for financial and creative reasons - was key to the advancement of the artform. Most fans learned through the mentoring of others and to rely on their community.

One fan remembers:

“Mary Van Duesen, who was a big, famous, important vidder on the East Coast, she used to, she was very generous with her time with people who were interested in vids and she would, you know, tell them about how to make vids, and sometimes have like little tutorials in her room at cons. And she invited me up to her house for one weekend, to see how she made a vid, and actually I’m credited on that vid. Although you know she totally made it, and I said, “Maybe that scene?” [laughter]… She was very generous with her time and expertise. Cause I would say, because now there are all these theories of mentoring.

If anybody was my mentor, she was my mentor.” Source: Media Fandom Oral Hstory Project Interview with Judy Chien)

A sample relationship map showing connections between some of the vidders over the decades. These connections varied: some fans collaborated creatively or inspired others to take up vidding, others shared only the VCR equipment or jointly distributed their solo creations on shared songtapes. Make your own node map

These fanvids and the collaborations that produced them were labors of love by and for women. In 1983, a fan wrote about her experiences at ZebraCon #3:

“The con was underway. Rooms filled with laughter and cigarette smoke. Wine flowed with love. Zines and stories and song tapes took our time… a song tape was born. The reward was given this year as we watch the results of your hours of hard work. ‘What I Did for Love.’ ‘Another One Bits the Dust.’ ‘Just to Feel this Love.’ ‘Forget Your Troubles, C’mon Get Happy.’… Give yourself a hand, Ladies. Your work deserves more.” Source: S&H #28 (Dec. 1981)

Stone Knives

Putting It All Together: Bearskins and Stone Knives

So working with fragile tapes, no fades/dissolves, 3rd generation quality videotape, a lack of audio editing, rollback erasing video, rainbow noise artifacts, machines that required manual starting and stopping, stopwatches, daunting economic costs, and fighting Macrovision as well as other hurdles imposed from TPTB, fans persevered and created a new artform.

In 1990, the vidding collective known as California Crew made a documentary-style video of them editing a fanvid together over a long weekend. The vid was called “Pressure”:

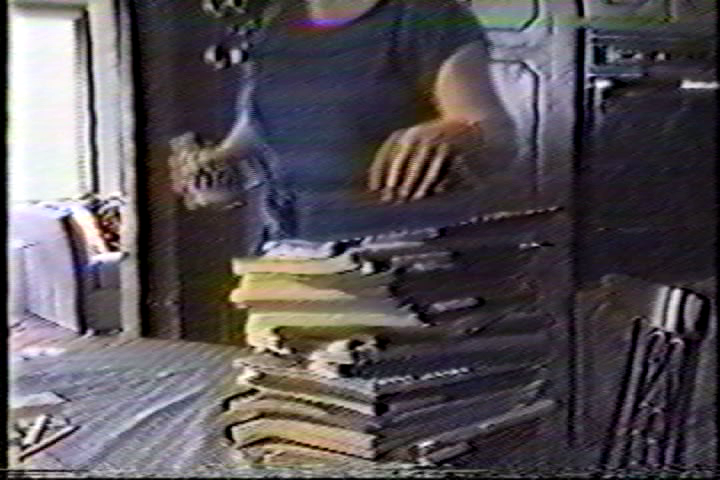

[It]….is composed of original footage, depicts the vidders getting together to make a Quantum Leap VCR vid over the course of a single weekend (a highly stressful event, hence the vid’s title.)Pressure is thus a rare artifact in that it documents the complexities of making of a VCR vid. The vidders time the song with a stopwatch, mark out the beats, watch, select, and measure all their clips in advance. The vidders work most of the vid out on yellow legal pads with calculators before actually assembling the clips on tape, laying them down in order. The audio track was imported last. The vid also documents other aspects of fannish subculture circa 1990: in the frame we see numerous cases of VHS cassettes and piles of fan fiction zines. Source: Fanlore: “Pressure”

Special thanks to Rache for her help and for MPH for her superb editing. And to Lim for putting it all together.